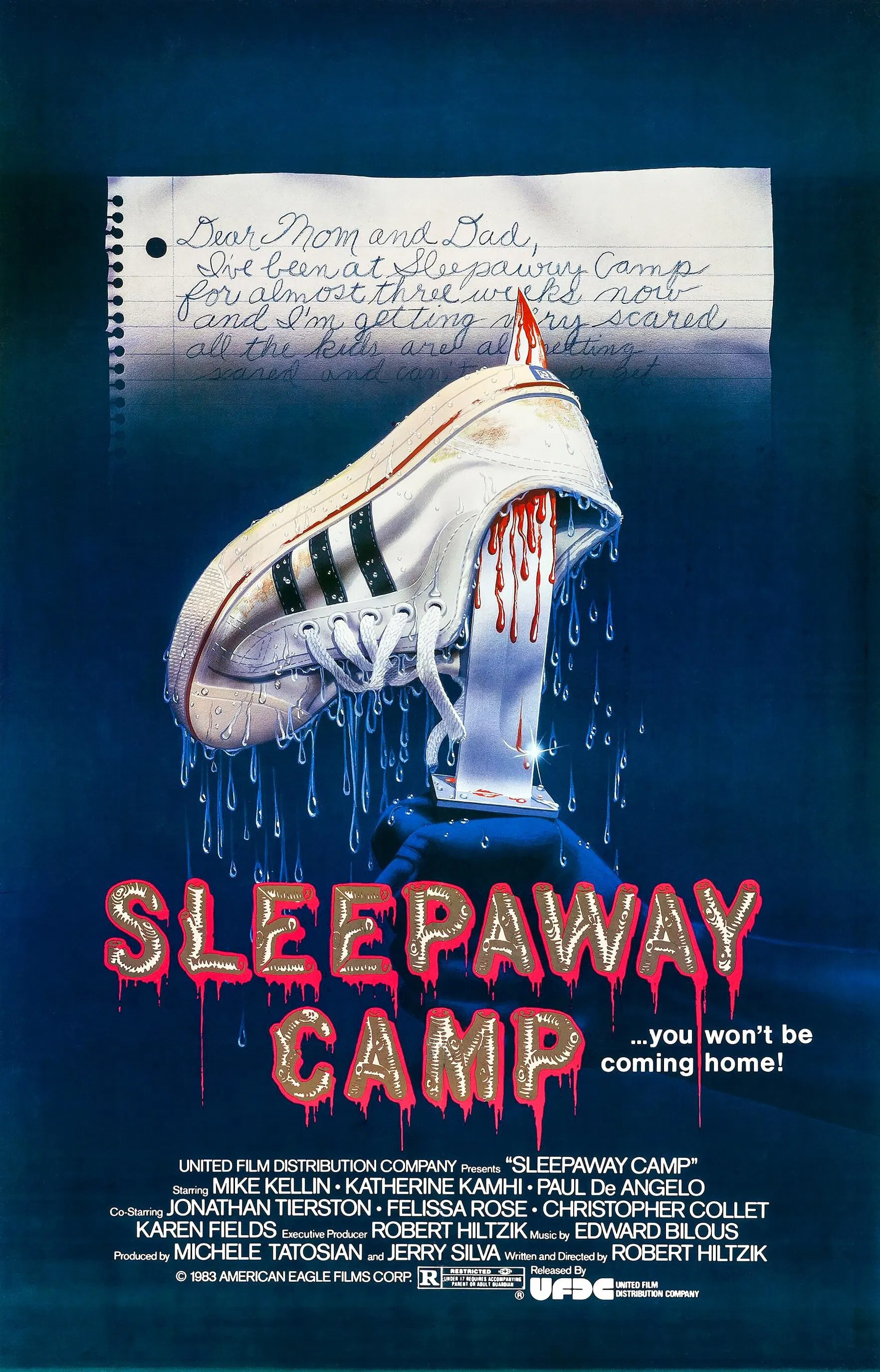

Sleepaway Camp (1983)

dir. Robert Hiltzik

Everyone wants to know if Sleepaway Camp is simply transphobic filth or secretly a manifesto of queer rage, but it defies both interpretations. I can’t seriously read the final shot as anything but a perverse attempt at shock value, a cynical expression of disgust. Angela’s masculine groans register on the same awful wavelength as Emilia Perez’s brief flashes of deep-voiced violence, an unmistakable implication of inherent, immutable manliness. But how do we square Sleepaway Camp’s bigoted ending with the film’s empathetic treatment of Angela? She is not the Son of Sam, not the vessel of Satan or the agent of the black dog. She is a Valkyrie, punishing only those she deems unworthy. Robert Hiltzik at least tries to understand the gendered anguish of swimming pools, volleyball courts, and locker rooms. That has to count for something, right?

The film’s sympathy for Angela clashes so harshly with its last-second twist that I wonder if Hiltzik only wrote Angela sympathetically to deceive the audience and enhance the twist’s effect. A transfeminine penis is one thing; a transfeminine penis attached to a character you liked is another. “She’s revolting—and you were rooting for her! Don’t you feel so gross?” Cisgender moviegoers can experience two forms of shock at once: the external shock of a trans dick, and the internal shock of having supported a queer. This is not the horror of gender apartheid and heteronormativity, but the horror of misplaced empathy—of a friend you thought you could trust, a girl you thought you liked. Who could blame you for squirming in your seat? Who could blame you for reacting the way you did? She tricked you.

Somehow, I did not know about the twist when I watched this movie. I’d added Sleepaway Camp to my watchlist because it reminded me of the “sleepaway camp” in I Saw the TV Glow. Well, I guess it all makes sense now, but I still can’t wrap my head around Angela. We could optimistically place her in the same dated-but-admirable category as Eli from Let the Right One In: unfortunately forcefemme, clearly written by a cishet man, but still the object of our understanding. Still the hero, or at least not exactly the villain. Whatever was going through Hiltzik’s mind (if anything), it’s undeniably radical to ask an audience in the eighties to care about a trans girl’s feelings, even if they don’t know it, and even if it’s in service of a dumb twist. Another movie might have paired Angela’s appearances with sinister music and harsh shadows across her face. She would have plotted her bullies’ demise with a deep, gravelly cackle. She would have cracked her big manly knuckles as she readied the murder weapon. She would have awkwardly fumbled every test of girlhood, as if the second X chromosome contains instructions on how to walk in heels and fold a fitted sheet. But Angela doesn’t do any of these things. Angela’s just a little shy. Weren’t you?

In fact, Angela’s femininity only grows as the film goes on. She’s weird at first, statuesque and silent, but Paul’s kindness opens her heart and unzips her lips. She finally speaks, and with a girl’s voice. She laughs and flirts, she enjoys Paul’s courtship, she forms a crush. Angela is excluded not because she isn’t good at girlhood, but because she’s reluctant, withdrawn, like lots of girls are. She suffers from a universal condition, and she acts upon a universal fantasy: revenge. Her rage boils and spills over. Her rage burns. At first, we applaud it, because a pedophile surely deserves death; because a ruthless bully might not deserve to die, but we don’t mourn them either. Only when she kills Paul—the boy-wonder, the all-American, the slice of apple pie—the boy your mom would probably like—only then does the film’s sympathy run out. Until Paul, Angela only punishes sinners. But is it a sin to pursue the girl? To ignore a rejection? To kiss her after she asked you not to?

In 2025, we would answer: it depends, yes, and duh. But in 1983? That’s different. Little boys in eighties flicks are always chasing girls around and negging them until they fold. Until they relent and kiss back. This is what boyhood is about, this is “romance,” this is the correct order of operations: boy hunts, girl runs; boy moves, girl retreats; boy kisses, girl is kissed. Maybe Sleepaway Camp hates trans women and thinks they’re all freakish criminals; maybe Sleepaway Camp loves trans women and supports their righteous homicidal anger; or maybe Sleepaway Camp thinks trans women are alright, but if you’re going to become a girl, you need to accept everything that comes with it. Kill all the child predators you want, but when Paul begs at your feet, give up and give in, because the alternative is unthinkable. The alternative is blood.

Something’s off at this camp. You smell it too, right? All the boys are showing midriff and squirming in the pile-up, muscular and horny. Is it the water? Is someone dumping hormones in the creek? Sleepaway Camp implies that Angela kills Paul because his kiss reminds her of the time she saw her dad having sex with a man, but what should that mean for Sleepaway Camp’s undeniable homoeroticism? At a fan Q&A in 2001, one audience member asked Robert Hiltzik what the deal was with those “naked men running around and being in bed together.” Hiltzik answered, “That’s called foreshadowing!” That’s right: Chekhov’s homosexual. A sweaty ruck of dudes in the first act and a traumatic memory of your gay dad in the third. Angela is bothered more by her late father’s sexuality than by her involuntary transness—just as Sigmund Freud intended. At no point does Angela shun femininity or express a preference for boyish things. There is no scene where Angela stands before two gendered bathrooms and hesitates, no choice between something blue and something pink. There is no detransition. In a way, maybe it’s progressive to reduce transness to a plot device, to treat it the same way horror movies have always treated sex, race, and class: as plot fodder. As character shorthand, as an accessory. As nothing all that deep.

What Robert Hiltzik meant to say couldn’t possibly be as interesting as what his film actually said. I don’t need to convict him of transphobia to talk about this film’s questionable messaging. This is a blog post, not a trial. This is a memory. This is a girl’s face superimposed on a nude man’s body, fade to green; this is Inland Empire’s jumpscare plus girl dick; this is the secret trans agenda. This is the social contagion, and it spreads through eye contact and good music. This is what happens when you expose your child to harmful rays and indie shoegaze. If gender dysphoria had a vaccine, RFK Jr. would make sure every child in America got it.

Could I get it too? I wish I had felt comfortable taking off my shirt around boys. I wish I didn’t remember that day at camp when the lifeguards made fun of my precocious body hair, and when my friend tried to console me. He said, “I’m sure some girls like that.” It did not help. I wish I didn’t remember that time in the tent when we all compared. I wish I hadn’t defended myself with humor and self-deprecation. I wish I hadn’t called myself an introvert even though I loved being around people, or dreaded gym even though I loved playing sports, or spent so long staring quietly into mirrors. Getting so close I could only see my eyes, then closer. Trying to push through the glass. Trying so hard to see another side that didn’t exist.

Angela responded with silence; I responded with loud noise.

Angela mimed; I clowned.

Same difference.