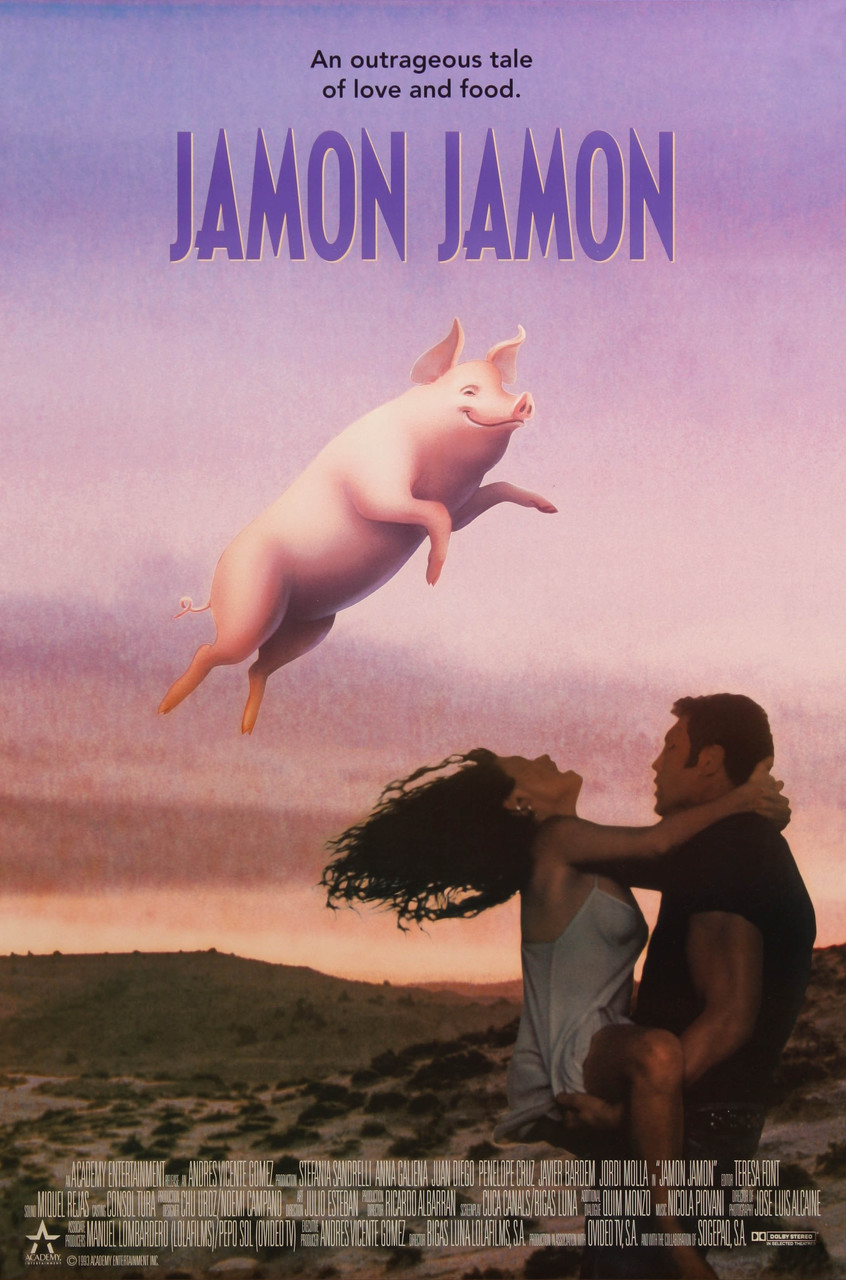

Jamón Jamón (1992)

dir. Bigas Luna

All hail the bulge. In grief and in ecstasy, in triumph and in tragedy, Javier Bardem, known in this film only as el chorizo, clutches not his face, not his heart, not the open Spanish sky, but his mountainous bulge. His real center, his root chakra, his jamón. I haven't seen the rest of Bigas Luna's Iberian trilogy, but the poster for Huevos de oro indicates that, alongside tit sucking, the mighty bulge is a consistent theme.

Everything in this film begins and ends with huevos. The cardboard huevos of a monolithic bull, which the petulant failson severs in a blind, cuckolded rage; the huevos, perhaps enhanced by some movie magic, barely fitting inside Javier Bardem's little shorts; the countless huevos cooked and made into piles of omelets by (and this is what they're actually called in the credits) la puta madre and la hija de puta, huevos once provided by Penelope Cruz's deadbeat, abusive, chicken farming father. In the bullfighting ring, Javier Bardem diagnoses his nervous, flaco friend with that same terminal illness that claimed la puta madre's husband: You don't have the huevos.

In this Spanish desert town, men are judged by their virility, and women are judged by their desirability. "It's been so long since I've flown," the executive exclaims as el chorizo takes her to bed. Left in the abyss by her immature fiancé, Penelope Cruz does not turn to her mother, her home, or her little sisters (who barely appear in the film, except to be shooed away before Cruz's mother chides her for getting knocked up), but to el chorizo. There, at the arcade machine, she finds bliss. There she finds a man who can run with the bulls. There she rides a real motorcycle.

And what did el chorizo want from her? He tells her: your tits. Your omelets. Earlier in the film, Cruz tells her betrothed that she doesn't want to make omelets for the rest of her life—but now, there isn't a hint of dissatisfaction or longing or resistance to her prescribed roles. All she needed, it turns out, was Javier Bardem's gran chorizo, and a rack of jamones. Finally, a man with the virility to match her desirability. (Sidenote: the other day, one of my old high school friends, who I haven't seen in many years, posted an AI-generated comic to Facebook with a similar message: "Women don't want weak husbands. Children don't want weak fathers. Siblings don't want weak brothers. Strength is not a choice, but an obligation." Although this friend is himself Puerto Rican and Black, the archetypal Real Man in the comic looked like the Aryan soldier from Triumph of the Will. Men are... not okay.)

In these sand dunes, in these underwear factories, love does not exist. Javier Bardem, intoxicated by the eggy taste of her nipples, announces that Penelope Cruz is the only woman he has ever loved, although it takes barely 30 seconds of persuasion for him to cheat on her. The characters in this film pretend to have grander motives, but the real guiding principle here is horniness. If you're a man, that is. Javier Bardem reluctantly slays the emasculated boy and grabs his groin in despair. The executive's emotionless, domineering husband creepily embraces Penelope Cruz in the Spanish sun (after possibly the most uncomfortable makeout scene of all time). But Cruz herself? Her mother? The executive? They're left with work. They're given the jobs of comforting, mourning, and fucking all these broken, dramatic men. They're passed around like cuts of fuckable meat, like so many legs of jamón. The romantic sunset and the swelling music seem totally oblivious to the chauvinism and brutality of the past 90 minutes.

Bigas Luna's camera admires Javier Bardem, but this is a purely heterosexual admiration. This film does not desire Bardem like Pedro Almodóvar's camera desires Antonio Banderas, or like Claire Denis's camera desires a tangled mass of sweaty Frenchmen. This film does not want to fuck Javier Bardem at all. No, this film admires men strictly in their capacity to (1) dominate other men and (2) fuck whatever beautiful women they encounter, even if it takes a few weeks of seduction and one medically frenzied pig. El chorizo even reminds the executive, the richest and supposedly most powerful woman in this film, that "I will do whatever I want." This is Kierkegaard's Diary of the Seducer with the philosophy sucked out. El chorizo is Johannes, if Johannes had an even cruder and more cynical view of the fairer sex and a craving for garlic.

Marilyn Frye put it far more eloquently than I ever could: "To say that straight men are heterosexual is only to say that they engage in sex (fucking exclusively with the other sex, i.e., women). All or almost all of that which pertains to love, most straight men reserve exclusively for other men. . . . Heterosexual male culture is homoerotic; it is man-loving." Penelope Cruz's brief resistance to the failson's touch in his car is, it seems, her last gasp as a human being. After that flash of personality, she never again expresses any desire other than her desire for good dick—a desire that she herself does not pursue. No, it is for the men to pursue, and for the women to warm up to the men. Yes, even to the pigs. Especially to the pigs.

In a story filled with pigs, only one pig is redeemed, and his name was Pablito. He's rolling in the great mud pit of the sky now. Rest in pork, amiguito.