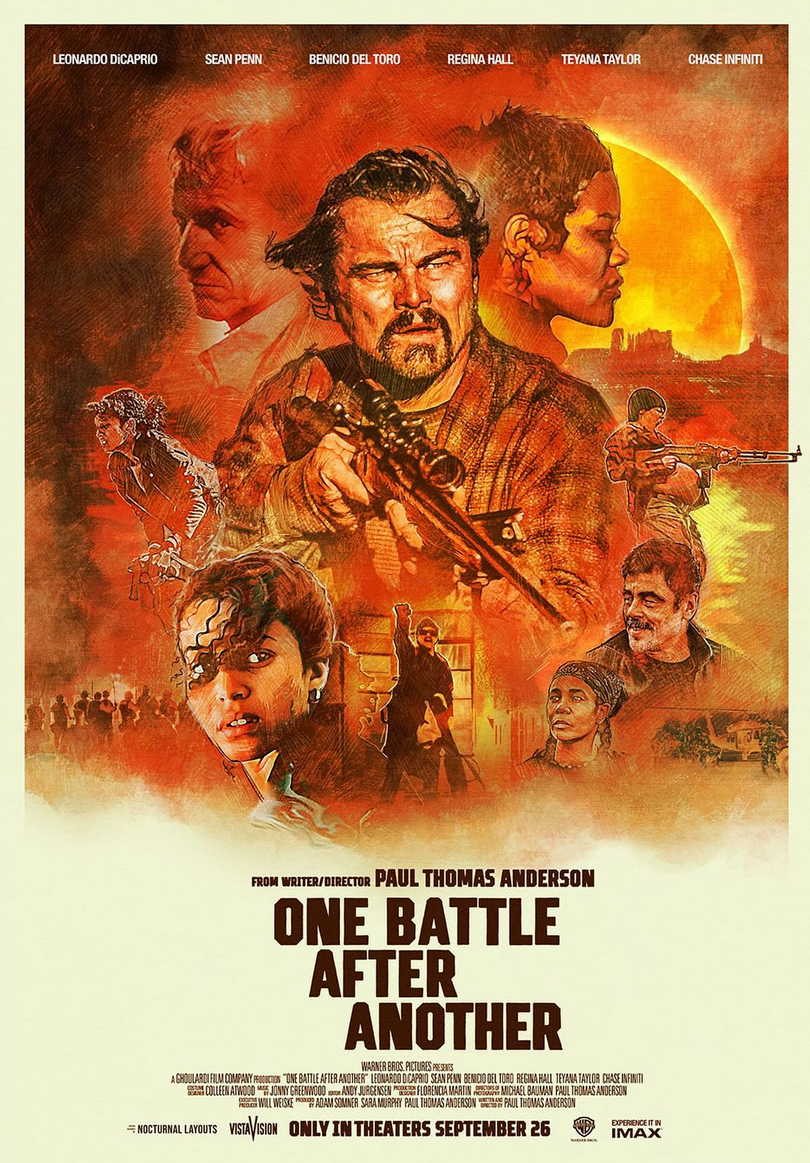

One Battle After Another (2025)

dir. Paul Thomas Anderson

“There is no articulate resonance. The common problem, I suppose, is to have more to say than vocabulary and syntax can bear. That is why I am hunting in these desiccated streets. The smoke hides the sky's variety, stains consciousness, covers the holocaust with something safe and insubstantial. It protects from greater flame. It indicates fire, but obscures the source. This is not a useful city. Very little here approaches any eidolon of the beautiful.”

Samuel R. Delaney, Dhalgren

⁂

“Perhaps if human desire is said out loud, the urban planes, the prisons, the architectural mirrors will take off, as airplanes do. The black planes will take off into the night air and the night winds, sliding past and behind each other, zooming, turning and turning in the redness of the winds, living, never to return.”

Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless

⁂

“I am standing puzzled, unable to decide whether the veil is really being lifted, or lowered more firmly in place; whether I am witnessing a revelation or a more efficient blinding.”

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

⁂

Here we are again, racing over repetitive hills, each for a different reason. One running away from death, one hunting her down, one following in drug-addled confusion—each catching a glimpse of the other at different points, never all three at once—the small flash of a dashboard, the bouncing echoes of revving engines—riding the asphalt treadmill of change. Remember that any three nonlinear points can be traced to form a circle. Remember that chaos is not lawless, but obeys its own set of laws. Consider the rights conferred by a loaded gun, and the duties prescribed by a barbed wire fence. Remember this: “the pace of oppression outstrips our ability to understand it.”

Thomas Pynchon writes: “A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.” Well, what do we have to compare this to? When American streets buckle under the unfamiliar weight of tank treads, what memories will console us? What experience can we depend on when windows in Chicago rattle from the sonic booms of fighter jets?

No matter how you spin it, no matter how many asterisks you affix, Americans have enjoyed a relatively charmed and peaceful existence over the past few decades. Already I hear banging at the door and angry shouts of exception. Yes America is built on violence yes America rests on a bed of bones yes America has a taste for flesh. Yes Thomas Jefferson wrote that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants,” for “it is its natural manure.” (He was referring to Shay’s Rebellion, a farmer revolt that the state militia put down by force, and which Jefferson himself had no part in. I guess it’s easy to shrug at violence in Boston from your luxury apartment in Paris.)

But America excels at compartmentalizing violence so that political majorities never have to grapple with it. After Reconstruction, we learned how to regulate our killing fields, how to bureaucratize our bloodshed so that most people have no idea what a whizzing bullet sounds like, or how to tell the difference between a blown exhaust and an execution. We are learning, though. We are making new memories in America, one suspected lynching, one shooting spree, and one domestic military deployment at a time. And we have nothing—nothing at all—to compare them to. We are lucky, and we are unprepared.

It’s silly now, maybe even condemnable, to call for faith in institutions. Why should we have faith in bodies that have, to their shame, failed to protect themselves? They must have seen this train coming, or at least heard the engine, and yet they dawdled at the tracks with their backs turned, not even brave enough to play chicken with it. They saw the approaching headlights and badly misjudged their distance and speed, and now is the split second before impact, when it’s almost too late to turn the wheel. It’s quaint to believe that clerks, office managers, judges, or agency heads will stand up to tyranny. Would you answer a call you’ve never received before? Would you recognize the black pupil inside the barrel of a gun? Would you know when to blink?

The accelerationists and the libertarians have agreed to a merger, FTC approval pending. To the revolutionaries, faith in law is the veil we must lift to become free; to the hesitant moderates, losing trust in the system is just a more efficient blinding. There is beauty in the past, or it’s an illusion; there is beauty in the future, or it’s impossible; there is wisdom in giving up on a false dream, or there is only shame in surrendering before someone makes you.

⁂

Not every narrative beat is a window into the author’s subconscious, and not every character is a statement beyond themselves. I don’t read Perfidia Beverly Hills as an inductive symbol for all of her parts—Black, woman, leftist, horny, Black woman, leftist woman, horny Black leftist, Black horny leftist woman, etc.—because One Battle After Another sprinkles each of these traits among several characters, giving the film at least plausible deniability when it unmasks Perfidia as a sex-addicted turncoat rat. That’s not to say that Perfidia’s character is unassailable, but some of the criticism regarding Perfidia (and by extension of the film’s racial politics, and by abstraction of Paul Thomas Anderson’s racial politics) strikes me as excessively personal and more than a little preconceived.

This is not your standard cowardly “it means what you think it means” Hollywood fluff: this film has a clear, unmistakable point of view, for better or worse. To his credit, PTA sets up his themes and sees them through. Where he focuses his attention, he is convincing, sincere, and sometimes even profound. But he’s also weirdly oblivious to the themes he did not mean to set up. Take, for instance, the lone confirmed queer character in the whole movie. They don’t get to have an arc; PTA doesn’t even grace them with a motive when they fuck over the main character. No, they voluntarily help the fascist state track down their rebellious friend, offering their cooperation after they’ve been allowed to leave the interview. (This is the only instance in the film of a character flipping entirely by choice, no ominous threats required.) The American Stasi commander never insults their visibly gender-nonconforming appearance, never derides their queerness, never belittles their identity; he treats them the same way he treats the pretty blonde cis girl.

Here we have one of PTA’s massive blindspots. Every fascist regime—every single one, ever, without exception—has hated queer people. Maybe this one does too, but apparently not as much as, like, the Bush administration. I guess you could assume that the Christmas Adventurers target queer people too, just based on their overall wretched vibes, and I guess you could assume that in the world of One Battle After Another, the government has already had its Hirschfeld Institute bookburning moment; but the text doesn’t give us very much evidence for it. Yes I am predisposed to notice this; yes I probably missed a lot of subtext regarding other oppressed groups; no I do not think I’m wrong to point this out.

In Licorice Pizza, PTA indulges in an offensive joke when it wasn’t really necessary (which I bring up just for purposes of comparison, not to indict him as a bigot or whatever); in One Battle After Another, though, he keeps it clean when an offensive comment would have been perfectly appropriate, when it would have been weird not to have one. (Well, that’s not entirely true. There is one instance of queerphobia in the film: when the leftist revolutionary protagonist calls the nonbinary character a “freak.” I don’t think this is wrong to include—blueblooded progressives are known to dip their toes in transphobia from time to time, and it’s hardly surprising that a middle-aged man, even a pothead rebel bomber hippie, would have some old-fashioned ideas about gender—but it contrasts sharply, very sharply, with the ruling fascist state’s unexpected silence on the subject.)

Queerness isn’t the only missing link in this film. Religion, too, plays a curiously backstage role to this whole thing. If a fascist regime ever takes power over this country (current fascist regime pending), it will derive its legitimacy at least partly from religion. An atheist American dictatorship is simply impossible. Maybe a fascist government could coast to power on religion’s coattails and slowly transition to a folkish civic faith a la Nazi Germany—even now, the government is jointly run by actual zealots and ironic Bible-thumpers with pagan Nordic tattoos—but it could never formally abandon the pretense of Christianity, not if it wants to stick around for more than a week or two.

So it’s interesting—and that’s all I’ll say about it, just “interesting,” because I really don’t know what to think about this—that religion only appears once in the film, when we visit a convent of revolutionary nuns. True, religious institutions can, and frequently have, served as a front of resistance to fascism; but I don’t recall seeing a single gaudy cross on the wall of the Christmas Adventurers at their annual Wannsee Conference. I guess their name implies some connection to Christianity. I don’t know, it’s interesting. Is Elon looking into this? Someone get Elon on this. Someone ask Baby Grok if liberals get into heaven.

⁂

Just how “fascist” is the United States in One Battle After Another? Is it Mussolini fascist? Is it Hitler fascist? Franco fascist? Is it a new syncretic form of fascism, a special brew of American revivalism, white supremacy, rape culture, and nativism? Is it just the Know-Nothings, but with iPhones and automatic rifles?

I haven’t read Vineland, but if I know anything about Thomas Pynchon, it’s that he never gives you enough information. He never allows you to breathe. You’re always guessing about what’s real and what’s not, what’s conspiratorial nonsense and what’s actually hiding in the shadows, what’s paranoia and what’s credible fear. You don’t know whether the soldier will pull the trigger on the unarmed civilian, because you don’t know if this is a military that still respects the rules of engagement. You don’t know if the Super Racist Club runs the whole government or only controls a few key players (still bad, but less bad), because no one in the story knows either. Rebellion is about projecting a greater force than you actually possess, while fascism is about pretending to be the underdog despite having all the power. Like I said in my review of Amarcord: fascism is a waltz and a half.

Pynchon came from an America obsessed with secret government projects, black sites, and psychological warfare. Pynchon witnessed the promising rise and devastating fall of a social revolution. The Beat generation wrote about the decline of hippie culture in their own insufferable, overrated way, but Pynchon had a different approach. For him, there was always another nesting doll to open, always another clue to follow to nowhere. You never find out where that muted horn leads, or who’s coming to buy lot 49. You never know what’s bona fide and what’s another fucking psyop. The end of the world is always today. The apocalypse is always now. There was a time to stop it, but it came before you were born.

PTA doesn’t leave us completely in the dark, though. He throws us a couple tiny bones of context, like disturbing posters in the middle distance and unseen helicopters and soldiers wearing “police” patches while they enter the sanctuary city warzone. The U.S. military runs the border in this film, not just DHS (which, I must remind you, is not supposed to be normal); it is impossible to reliably distinguish between civilian police forces and the armed forces; no one offers or expects due process after being detained; the villains never roll their eyes at accusations of fascism, apparently unbothered by the label; resistance fighters have built VC-style tunnels and railroads and bunkers while showing no signs of prepper delusion; a military officer has authority over domestic law enforcement in whatever jurisdiction he pleases; high school students don’t react much when camouflaged men enter their gymnasium and individually interrogate them. This is fascism. It doesn’t have swastikas or pencil mustaches or giant banners saying OBEY. No one has to attend Two Minutes Hate. And yet, this is obviously fascism—a gross mutation of fascism, filling the negative space around American individualism and the gospel of wealth.

Hence the ineffectiveness of warning that “it can happen here.” No, it cannot happen here, not like that. American culture could never tolerate European fascism on the ground level. Something can happen here, something unthinkable and dark and cruel, and the results of fascism, with which we are all sadly familiar, can happen here. But it will look different here. It will not wear red armbands. It will not goose-step. It will display itself another way; it will march in another style; it will heil the fuhrer, but not quite like they did at Nuremberg. America will do it in golden ballrooms, not cathedrals of light. America will make space glam. We don’t need the Protocols of the Elders of Zion for our fascist ideology; we already have Guns & Ammo magazine.

⁂

“What do We mean by the Revolution? The War? That was no part of the Revolution. It was only an Effect and Consequence of it. The Revolution was in the Minds of the People, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen Years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington.”

John Adams

⁂

For two hours Leonardo Dicaprio shuffles through tunnels and falls off rooftops in search of Revolution. He stumbles into a pocket of organized resistance but fails to recognize it as such, too singularly focused on the answer to a silly leftist riddle to acknowledge the Revolution around him. Just to make sure the audience understands the message, Dicaprio argues on the phone with an annoying tankie, whom Dijon coolly reprimands. This film does not believe in mystical communism, where sufficient faith in your fellow proletariat will nourish the soil and cause your crops to grow faster. It’s not an innovative theme, but it’s still effective (if a bit overindulged). At the very end, it even becomes hopeful and heartfelt—a soothing balm for this dismal and insincere moment in history.

That’s the most exhausting part of all this. No one is sincere anymore. No one in charge of this country holds any particular convictions or pursues their beliefs with any amount of backbone. I wrote in my review of Ron Ormond’s The Burning Hell that the right wing resists all psychoanalysis, because the right wing has no fixed constellation of beliefs, no consistent or predictable principles that would allow us leftists and libtards to “understand” the right. The right wing doesn’t move towards any particular vision of society, instead exhibiting something like Brownian motion—constant twitching, sudden dashes in random directions, instinctive responses to the environment. The conservative agenda is not as simple as “the opposite of whatever the left is saying this week,” but it’s something similar. A negative space; an inkblot; a tree in an odd shape, suggesting obstacles to growth that aren’t there anymore. Scar tissue from an injury no one remembers. So the right wing can never advocate with sincerity: it must always dress its wolfish desires in sheep’s clothing, it must always push boundaries of social acceptability under the guise of irony. Sieg heil, but only for the lolz. Blood and soil, but with your fingers crossed. National suicide, but as a mean prank (gone wild) (18+ mature) (she CRIES!).

Aren’t you tired of it? Aren’t you sick of podcasts and the Great Reddification of political discourse? Everything is a reference. Reacting sincerely to a horrible comment means you didn’t get it. We say nothing to each other, and we like it that way. No one breaks kayfabe.

I praised this film for committing to an actual message. But One Battle After Another also slides occasionally into ironic eye-rolling and bland Internet politics. I could have done without it. I also could have done without some of the film’s extremely superficial characterization, especially as it relates to sex and kink as a driver for political action. Amarcord had more to say about sexual politics in 1973 than this film did in 2025—probably because this film really isn’t interested in sexual politics, instead treating sexual desire as a stand-in for irrationality in general, as an excuse for characters to act against their interests and create narrative tension for its own sake. It works as long as you don’t think very hard about it. What does Perfidia mean for revolution? What does a rebellion kink mean for life under fascism? I know PTA isn’t suggesting an equivalence between Perfidia’s desires and the inherently Freudian motivations of fascism, but the film could have easily led to that conclusion. PTA flirts a lot with parallels and equivalences in this film—effective narrative devices, essential tools for character work, but tough medicine for a political story, and hazardous when Nazis are party to the comparison.

What PTA does in One Battle is admirable, but also a little disappointing, like running quickly across a bed of hot coals. Still impressive, still brave, but… not as cool as walking slowly, you know? There’s a difference between confronting pain and mastering it. One Battle confronts pain, but does not master it, and for that it deserves a gentle round of qualified applause.