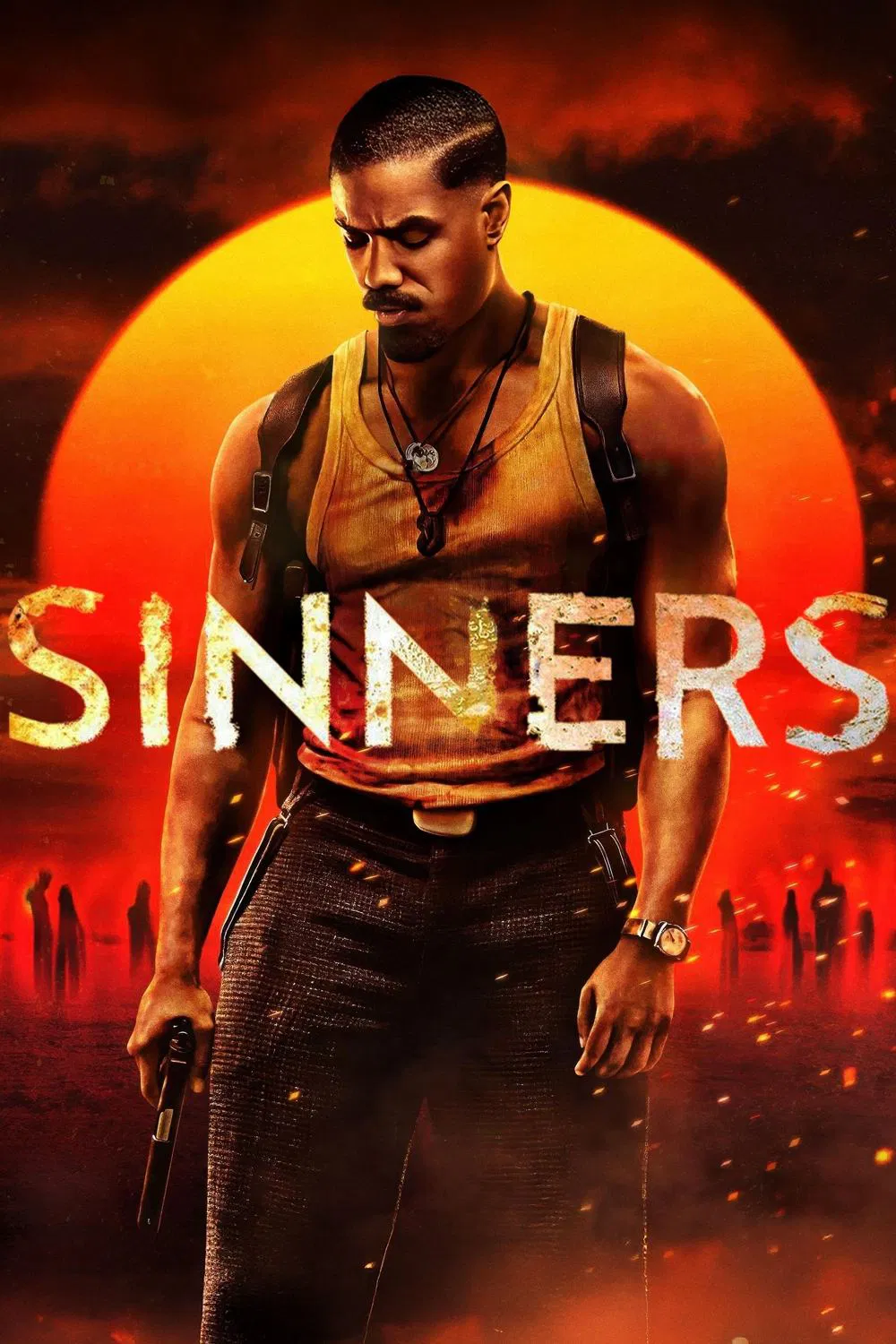

Sinners (2025)

dir. Ryan Coogler

Nat King Cole didn’t get to finish his concert in Birmingham, Alabama. “I just came here to entertain you,” he said. “I thought that was what you wanted. I was born here. I can’t understand it.” A car full of guns and brass knuckles parked outside the venue doesn’t leave much to the imagination, but could you blame the King for being surprised that white people, the same people he’d generously introduced to good music, would rush the stage and try to kill him in the middle of a performance? He searched for answers: “I have not taken part in any protests. Nor have I joined an organization fighting segregation. Why should they attack me?”

Thurgood Marshall suggested that if he was going to keep playing all-white clubs and staying at segregated hotels, the King should pick up a banjo and complete his transformation into Uncle Tom. I can’t tell you if King Cole ever deserved that label, but Mr. Civil Rights had a bigger point to make: Americans—even smart, socially conscious ones, even ones with a sun-bleached “I’m With Her” bumper sticker on their Suburu and a recurring annual donation to Black Lives Matter—have this strange delusion that you can opt out. That if you’re not a card-carrying member of the Klan or the White Citizens’ Council or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference or the Nation of Islam, you can reach for the sky and protest your innocence, secure in the knowledge that you did what you could. You can "just" be a singer. You can "just" entertain.

“There’s no more Klan,” the amiable farmer assures Michael B. Jordan. Sure, the Klan had slipped a little by 1932, shrinking from over 5 million members in the roaring twenties to “just” tens of thousands during the Great Depression; and sure, the title of Grand Wizard had lost some prestige since that chilly Thanksgiving night on Stone Mountain, 1915. (They didn’t wear Knights Templar crosses and pointy white hoods in 1956 when they drowned the majority-Black town of Oscarville, Georgia and named the resulting lake after a Confederate soldier-poet, but I digress.) It makes you wonder: if a movie could inspire the Klan’s second birth, could a movie cause the Klan’s second death? Apparently not. Mr. Griffith won’t save us, and he made it perfectly clear that Intolerance was not an apology. Over a decade after the Klan's revival, Buster Keaton had to revise his big Civil War train heist movie to make the Confederates the heroes, because studios thought contemporary audiences wouldn’t accept a movie that glorified the damned Yankees, not with Reconstruction looming so large in the rear-view mirror. At last: wholesome Judeo-Christian values. At last: real progress. With alcohol prohibited, only blood could slake America’s thirst.

But careful: the shocking barbarity of the past is a ruse. We build monuments to Harriet Tubman, Emmett Till, and Rosa Parks and dust off our hands, satisfied that we’ve added a little melanin to Mount Rushmore—but it’s an elaborate act of denial, a mass coping mechanism. My third grade teacher (this was near Atlanta in 2006) brought me up to speed on what she called the “War of Northern Aggression,” and on the surprising upsides of chattel slavery (“at least they had free housing!"). Easy to file her under “bigots of Christmas past” and move on; not so easy to remember how in 2009, I mimicked my parents’ anger that my fifth grade teacher, a Black woman, showed us Obama’s inauguration live on TV (an event which, for white moderates everywhere, became a convenient signpost for the definitive End of Racism). Easy to say I simply had no politics back then, that I was an innocent sponge, a blameless mouthpiece for generational hate; not so easy to remember playing devil’s advocate during a U.S. History class discussion on whether Michael Brown deserved to die in the street. Easiest to pretend that confessing sin can redeem me from it; hardest to admit that redemption doesn’t work that way, especially not for nonbelievers like me. Beware the mirror: irony quickly becomes sincerity. Reflections quickly become reality. Bloody Mary doesn’t care if you believe in her. She shows up all the same.

⁂

Let’s collaborate. Let’s write a book called The End of History and the Last Black Man and put a big picture of Ben Carson on the front cover. Up yours, Francis Fukuyama. Up yours, Her Innocence Dolores Dei. Up yours, Pod Save America. Honestly, up mine. But Mary, little Mary (not so little anymore): now that is a true Ally. She’s read The New Jim Crow twice. She fully agrees with Ta-Nehisi Coates on reparations. Scroll down her Instagram page and find the captionless black square she posted five years ago, pixel-proof that she would’ve marched behind Martin in Selma if she could, a white speck in the background of your history textbook. God, all this righteous solidarity is making me drool. What? You want some, baby?

Just one drop of your blood, just one tiny taste of your soul, that’s all we ask. We need your music, Sammie. My vampiric Human Instrumentality Project will solve racism forever. One teaspoon of color in a vast sea of pale mayonnaise—one soul diluted to nothing, reduced to chalk. Remmick just wants to learn how to speak jive and do the lindy hop. He’s bored of the Celtic dances, he’s tired of intentional famines and royal British bullets, he believes in equality like a crow believes that every roadkill is equally delectable, like a worm equally hungers for every corpse at Gettysburg. He yearns for the bland unanimity of the graveyard, for the sweet obliteration of death. Remmick wants more than Carter family values. He wants to hurt his way to the blues like Delta Slim. He wants to conjure spirits and testify to his woes like bright-eyed Sammie, like blind-eyed Willie Johnson. He craves electric guitars and West African rhythms, slave songs and rock 'n' roll. God, Remmick just wants to live. He wants to believe that the circle will be unbroken, by and by, Lord. Mary doesn’t even want to be white, Stack! Oh, you know she’s invited to the cookout. She’s risking her social standing as a white-passing woman; Stack’s risking his life and the lives of everyone he loves. All’s fair in love and anti-miscegenation laws—in war and one-drop rules—in Clarksdale, Mississippi, 1932, one year before FDR tells America what it should fear.

Like Kimbley maintaining his individuality among the tempest of tortured souls inside the Homunculus Pride, Stack holds onto some of his Blackness even after joining with the monocultural hivemind. There’s an argument to be made for just giving up and giving in. There’s an argument to be made that Jazz Is Dead. Nancy Pelosi has donned the kente cloth and kneeled beneath the Apotheosis of Washington, thus healing America for ever and ever. Amen, alleluia, we (who?) have (when?) overcome (what?). LBJ signs the Civil Rights Act, then crosses his fingers behind his back and sends another 10,000 troops to Vietnam while MLK preaches against reckless American imperialism and receives a letter from the FBI gently suggesting that he kill himself. Peace and love.

I guess what I’m talking about here is original sin. A stain that can never be washed away or rubbed off or bleached out. America has committed at least two: slavery and genocide. But then Strange Fruit trended as a TikTok sound, and these United States were finally cleansed of prejudice. White people shook their legs to Elvis and bought Miles Davis records, Ryan Schreiber wrote that Pitchfork review of a John Coltrane album (“We was sittin' there watchin' the stage…”), Beyoncé got her Grammy for best country album. The secret order of Choctaw vampire hunters could finally disband. They have completed their ancient mission.

The dirt has piled on so thick you can’t hear the crunch of bones when you walk anymore, the varnish so dark you can’t find the bloodstains on the walls of your luxury plantation wedding venue, the memory so faded you can’t remember where you dug up that Civil War bullet. Imagine falling in love on this dirt. Imagine singing and dancing here. Imagine the constant smell of death. Imagine orange lanterns in the woods, the wide open sky, and the terrible rhythm of hooves. Thump, thump, thump. Can't hide forever, Friday.

⁂

All the grave markers, all the crude headstones—

water-lost. Now fish dart among their bones,

and we listen for what the waves intone.

Only the fort remains, near forty feet high,

round, unfinished, half open to the sky,

the elements—wind, rain—God’s deliberate eye.

⁂

Near the end of Glory (1989), Morgan Freeman leads a regiment of Black Union soldiers in the blues. It’s the night before battle. They will all die, and they know it. He coaxes Achilles out from his tent and shows him how to squeeze his legendary rage into twelve short bars. Blues straddles major and minor, doesn’t shy away from the flat fifth that European music once called the Devil. Delta Slim doesn’t think Sammie’s suffered enough for the blues. What Sammie offers that night isn’t exactly joy, but it isn’t exactly suffering either. It’s a spell. It’s a message from beyond the Veil. There are tales of people who can share that message, and of people who want to suck the message away before it even escapes your throat.

The Ally nudges your shoulder and warns: Don’t stick around after sundown. Don’t tempt them. They’re summoned by the music, compelled by the great empty silence in their hearts to destroy it... and you have one delicious voice. Better not to use it.

Better to stay silent.